This

story was adapted from "Ghana's Rabbit Project." (Anonymous

author)

Africa Report. January-February 1979.

(Photos provided by S.D. Lukefahr).

|

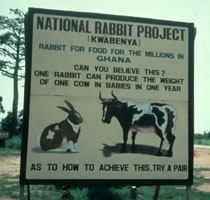

"Get the Rabbit Habit!" "Make the Bunny Money!" From the capital city of Accra to northern areas bordering on the Sahel, the catchy jingles sing out from Ghana's radios and television sets. "Grow Rabbits, Grow Children." "Rear Them, Control Them, Use Them" - along the roadways and in public squares, and advice is blazoned across colorfully illustrated billboards and posters. The publicity is part of a nationwide multimedia communications campaign backing Ghana's National Rabbit Project, which promotes backyard rabbit breeding as a self-help means of increasing meat supplies at low cost and with a minimum of extra effort.

|

The rabbit project is part of Ghana's nationwide drive to achieve food self-sufficiency to which the government has been committed for several years. Though the country now produces all of its own rice and nearly enough corn to meet requirements of its more than nine and a half million people, there is still a chronic shortage of meat. When animal products do find their way to market, they are priced far beyond the means of the majority of the population.

Rabbit food is readily available in Ghana. The animals will eat almost anything, including table scraps, leftovers from sugar cane harvests, various kinds of grass, and other local flora such as groundnut and sweet potato vines. Dried cassava provides good bulk for their diet, and brewer's mash, left as a residue from millet beer and formerly discarded as useless, furnishes an excellent source of protein.

In Ghana, the wild native "rabbit" has always been highly prized by villagers, though these days it is very difficult to find. Any backyard breed which managed to gnaw through its cage would soon find its way into a stewpot!

Besides food, other uses of rabbit

might also be of economic benefit to developing countries. Rabbit fur

is a main ingredient of felt, and pelts can be used to make hats and coats.

The brain is used in making a blood-clotting agent widely used in hospitals.

Fine rabbit leather, or vellum, has the ideal tension and quality required

for tiny drive belts used in tape recorders and other delicate machines.

The originator and director of Ghana's National Rabbit Project is Newlove Mamattah, a former adult educator who has had a consuming interest in rabbit breeding for more than 38 years. Mamattah's work, which began in his own backyard, has attracted considerable international attention. Currently, he is general secretary for developing countries of the World Rabbit Science Association.

Since the wild local rabbit is a small animal, weighing approximately two pounds, the development of hybrids yielding more meat, but hardy enough to do well in Ghana's varying climactic conditions, has been a prime objective. The Swiss government provided 120 rabbits to get Mamattah's project under way, and other exotic breeds have come from Australia, Belgium, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the United States. Breeding is scientifically controlled, and the ear of each rabbit is stamped with a serial number documenting its parentage.

Though Mamattah's project continued to generate interest, Ghana's Ministry of Agriculture did not give it any support until Joseph Ascroft, a Malawi national on leave from his post as professor of communications in the School of Journalism at the University of Iowa, arrived on the scene. In 1974, Ascroft came to Ghana as project manager of a multimedia "information Support Unit" and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), helped set up within the Ministry of Agriculture. One of the first duties was to find projects in need of communications support so that he might apply various techniques, training Ghanaian communications workers in the process. Believing in Mamattah and his rabbits, Ascroft persuaded the ministry to "let him make all his mistakes" on the endeavour before tackling the projects to which they were committed.

"They ate the stuff," says

Ascroft. "They thought it was chicken. They wondered to what expense

I'd gone to buy only chicken breasts." When the truth was revealed

at the end of the party, the new commissioner was very impressed. "Excellent!"

he exclaimed. "Is this one of my things?" "Yes, this is

one of the big campaigns," came the reply. "Suddenly all the

reservations against rabbit meat disappeared," says Ascroft.

"With chickens you're always

working backwards," says Ascroft. "In one typical case, only

49 chickens remained out of 100 day-old chicks after three months. With

rabbits the opposite happens - 50 rabbits had multiplied to 120 over the

same period. So we've forgotten all about chickens."

References on the National Rabbit Project:

Anonymous. 1979.

Ghana's rabbit project. Africa Report, January-February 1978, pp. 47-48.

Lukefahr, S.D. 2000. The National Rabbit Project population of

Ghana: a genetic case study. In: Workshop on Developing Breeding Strategies

for Lower Input Animal Production Environments, September 22-25, 1999.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, Rome. ICAR

Tech. Series No. 3:307-318.

Lukefahr, S.D., J.K.A. Atakora, and E.M. Opoku. 1992. Heritability

of 90-day body weight in domestic rabbits from tropical Ghana, West Africa.

J. Hered. 83:105-108.

Mamattah, N. 1978. Sociological aspects of introducing rabbits

into farm practices. In: Workshop on Rabbit Husbandry in Africa, December

16-21, 1978. International Foundation for Science (IFS), Stockholm. pp.

93-99.

Opoku, E.M., and S.D. Lukefahr. 1990. Rabbit production and development

in Ghana: The National Rabbit Project experience. J. Appl. Rabbit Res.

13:189-192.

Owen, J.E. 1981. Rabbit meat for the developing countries. Wld.

Anim. Rev. 39:2-11.

Owen, J.E., D.J. Morgan, and J. Barlow. 1977. The rabbit as a producer

of meat and skins in developing countries. Rep. Trop. Prods. Inst., G108,

V.

Technoserve. 1975. Project Study: National Rabbit Project - A Rabbit

Production Enterprise. Project Reference No. 3/12/0115. August 1975, pp.

1-57.